Rodrigo Amado / Chris Corsano

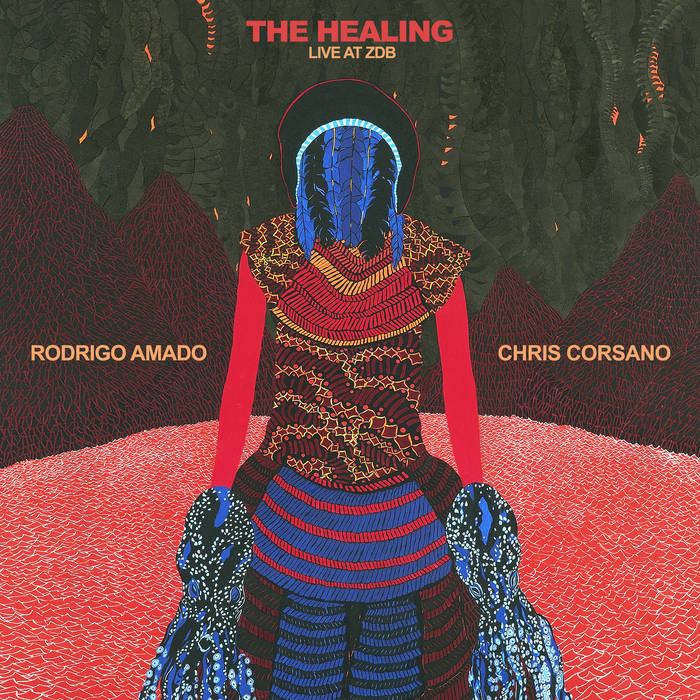

The Healing

Zwischen Klanggewittern und zarten Zwischentönen

veröffentlicht am 4. August 2025

Rodrigo Amado tenor saxophone

Chris Corsano drums

Recorded by Cristiano Nunes at ZDB, Lisbon, September 22nd, 2016

Mixed and Mastered by David Zuchowski

Produced by Rodrigo Amado and Luís Lopes

Cover painting by Rui Moreira – “Telepath III”

Photos by Vera Marmelo

Cover design by Rodrigo Amado

von Rodrigo Amado & Chris Corsano

Rodrigo Amado – tenor saxophone

Chris Corsano – drums

Beim Lesen der Rezension von Troy Dostert auf Allaboutjazz ging es mir durch den Kopf: Ich würde gern mal eine Kritik zu Kritiken verfassen: schau: Unter den jüngsten Partnerschaften im Bereich der freien Improvisation ist das Saxophon-Schlagzeug-Duo Rodrigo Amado und Chris Corsano eines der dynamischsten und mitreißendsten im Bereich freie Improvisation – wie will man so etwas messen? Ich ahne schon: er will seinen Superlativ loswerden und seine Begeisterung: aber sie hier, das Duo, immer gleich über alle anderen stellen – ich weiß immer nicht, ob ich da lachen oder weinen soll. Etwas, worüber im Jazzdiskurs zu wenig reflektiert wird: die Sprache der Rezensionen selbst.

„Eines der dynamischsten und explosivsten Duos im Bereich freier Improvisation“ – das ist emotional aufgeladen, wirkt aber schnell absolut setzend, als würde ein objektiver Maßstab existieren – so ein Superlativ behauptet mehr, als er je belegen kann. Ich selbst wurde ja ebenfalls mehrfach dabei erwischt, wie ich zu emphatisch, zu hingerissen oder zu emotional auf Aufnahmen reagiere, so enthusiasmisiert mal wieder … der Gebrauch der Superlative lässt schnell eher Rückschlüsse auf den Rezensenten als auf das Rezensierte zu, auf das vorliegende Beispiel bezogen: Superlative und große Begriffe (explosiv, wichtigstes, bahnbrechend) werden genutzt, um Aufmerksamkeit zu erzeugen oder einen Text zu heben, es dreht sich das Reputationskarussell: Namen wie Amado oder Corsano sind in bestimmten Zirkeln gesetzt. Wer dann eine neue Platte bespricht, schreibt auch in gewisser Weise im Schatten ihrer bisherigen Rezeption – da will man nicht untertreiben.

Auch laufen solche Jubelstürme häufig Gefahr, genau das Gegenteil zu bewirken: was der Rezensent feiert, bekommt plötzlich eine Art Abflughöhe, unter der jedes weitere Hinhören hindurchtaucht und die Aufnahme somit erledigt, ohne sie zu erwischen. Kritik wird zur PR und Superlative ersetzen echte Beschreibung, so bleibt von der Musik nur der Lärm im Vokabular. Oder: Wer alles zum Superlativ erklärt, macht am Ende nichts mehr hörbar. Oder: Wenn Adjektive die Töne umstellen, aber das Tor nicht sichtbar wird. Oder: Wenn Adjektive die Töne umschreiben wollen – aber den Ton nicht teffen.

Wir prüfen also die Aufnahme selbst und stellen fest: die Begeisterung über das Album The Healing ist durchaus nachvollziehbar: was ein Energieaufwand, was ein Dialog zwischen Schlagzeug und Saxophon. Man spürt, wie es knistert in der Luft, ohnehin eine großartige Besetzung: nur Schlagzeug und Saxophon. Das haben wir in Berlin häufiger, vielleicht noch ergänzend mit Klavier oder Gitarre – das ist, was Aufnahmen erst sicht- oder hörbar machen, da das Live-Event an sich schon energetisch fordernd ist und du nicht alle Nuancen speichern kannst, mit der Aufnahme aber jedes Detail nochmal prüfen.

Insofern eine Gratwanderung für jede Rezension: Den Ton so zu treffen, dass eine echte, direkte Hörerfahrung entsteht, die nicht nach Superlativen sucht, sondern in Beziehung tritt mit dem, was da geschieht. Saxophon und Schlagzeug – ein Dialog ohne Netz, ohne harmonisches Rückgrat, ohne Sicherheitsseil. Wenn das funktioniert (wie bei The Healing), entsteht dieser elektrisch aufgeladene Zwischenraum, das Knistern in der Luft. Die Aufnahme macht Nuancen überhaupt erst sichtbar. Was dort geschieht – körperlich, klanglich, kommunikativ.

Manchmal braucht man erst die Distanz der Aufnahme, um wirklich alles zu hören: das Atemholen, die Pausen, die Mini-Verschiebungen im Puls. Was live durch Energie überstrahlt wird, tritt im Nachhinein als fein gezeichnetes Mikrodrama hervor.

Was sich hier zwischen Saxophon und Schlagzeug entspinnt, ist keine konstruierte Virtuosität, sondern ein Gespräch, das vibriert vor Spannung, Irritation, Nähe. Berlin kennt solche Formate: zwei Körper, zwei Klangquellen, keine Harmonie im Rücken, nur Luft, Haut, Metall. Die Aufnahme hilft zu hören, was das Live-Erlebnis überfrachtet – aber nie ersetzen kann: die Nähe, das Knistern, die Fragilität. Zu hören (und zu sehen), was zwischen den Tönen liegt.

Das erste Stück, Titel gebend The Healing Day, nach 24 Minuten hängst du in den Seilen, ein Punch ist das, unglaublich, Rodrigo Amado schließt das Stück auf dem höchsten Ton ab, im Hintergrund feiert das Publikum, Gänsehautmoment – The Cry, das zweite Stück, beginnt wieder in den obersten Regalen, ist nur neuneinhalb Minuten lang, das Saxophon der obersten Regallage wechselt auf die mittlere Ebene und wird von ersten Rasselstimmen, Geläut und Trommelwirbel begleitet – sie spitzen sich gegenseitig an mit Lauf und Wirbel der Drums und irgendwie unfassbar klirrendem Saxophonton – die Drums scheinen wie hinter einem Klangvorhang, nicht vorne, sondern hinter dem Geschehen, sehr schöne Interpunktionen und Wechsel dort.

Ein innerer Monolog entsteht, ein Essay, eine Bildbeschreibung zu einem Idealzustand: Das Verschwinden im Dickicht der Töne oder im Wirbel der Trommel, nach den ersten 23 Minuten fühlst du dich durchgearbeitet, durchgeschüttelt und durchgerungen an, dieser Abschlusston da oben ist irgendwie über dem Körper, nimmt dir die Luft, entzündet sie, entfacht sie, durchstößt sie, dann The Cry, wieder dort oben, neuneinhalb Minuten, nur ein Bruchteil der ersten Aufnahme, aber wieder genauso aufgeladen, nach dem hohen Beginn wechselt Amado eine Ebene tiefer, die Drums begleiten erst mit Rasseln, mit Glocken, mit kleinen Impulsen – nichts drängt sich vor, alles spitzt sich zu, in Läufen und Wirbeln, es ist, als würden sie sich gegenseitig aufschaukeln, zwei, die kämpferisch vibrieren. Corsanos Schlagzeug bleibt wie hinter einem Vorhang, nicht in vordergründiger Präsenz, sondern als Textur, dann schiebt er sich doch noch allmählich nach vorn, auf halbem Weg des Stücks beginnt der Körper des Sets zu sprechen, nicht nur Becken und Trommel, sondern auch Puls und Fläche, Interpunktionen wie choreografierte Atemzüge.

Ich frage mich oft: Wie ist das physisch möglich? Wie kann jemand so spielen – und dabei noch hören, fühlen, reagieren?

Wir hören das dritte Stück, Griot – ich weiß nicht, wie das beschreiben. Die ersten drei Minuten rüttelt, trommelt schüttelt Corsano sein Schlagwerk – man müsste in Erfahrung bringen, was da alles für Utensilien noch mit eingesetzt werden, das ist schon sehr viel allein für diesen Soloantritt, der dann stochernd, auch stotternd, schließlich deutlich nuancierter und dann sogar gesprächig, dann wieder launisch oder auch bewusst provozierend aufgenommen wird vom Saxophon, sie steigern sich wieder ins Überphysische, vielleicht auch Hyperphysische – je länger ich das so höre, desto mehr verstehe ich, warum Troy Dostert dies Duo und mit ihm die Aufnahme so zu überhöhen versteht, das ist tatsächlich unglaublich energetisch und tatsächlich sehr weit oben alles, man wird schier rasend gemacht.

Das Chaos, die feinen Zwischentöne. Fast schon rituell. Ein Trommelsolo, das nicht nur auf Rhythmus macht, sondern ein ganzes Arsenal an Sounds und Texturen entfaltet. Corsano arbeitet nicht nur mit dem Schlagzeug, vielmehr schafft er lauter Klangobjekte, die wie kleine Überraschungen wirken. Stochernd, stotternd, gesprächig, launisch, provozierend – auch das Schlagzeug: ein faszinierender Mix aus Gegensätzen und emotionalen Typen. Ein Dialog, der kämpft und flirtet gleichzeitig, ein Wechselspiel aus Herausforderung und Einladung.

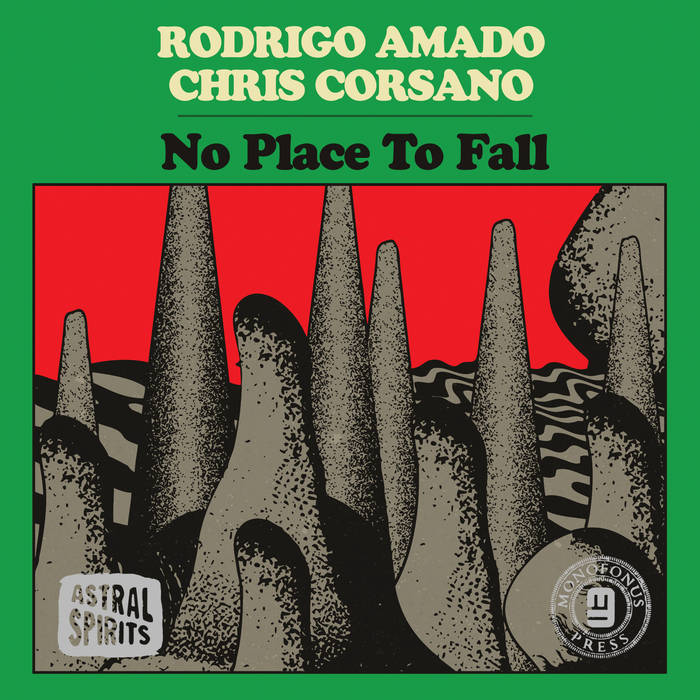

Die Musik sprengt den normalen Körper-Raum, es fühlt sich an, als würden sie die Zuhörenden entgrenzen, sie auf eine andere Wahrnehmungsebene katapultieren – wilder, intensiver, fast schon transzendental. Und man als Rezensent gar nicht anders kann, als in Superlativen zu sprechen, insofern. Meine Absicht, einmal eine Kritik über sich selbst überladende Kritiken zu schreiben, mündet angesichts dieser Aufnahme in einen emotional überladenen atonalen Ausbruch – die Aufnahme fängt eine rohe, ungefilterte Kraft ein, die schwer zu fassen ist. Und laut Troy Dostert sei das hier vor allem ein qualitativ hochwertiges Erleben, das Album No Place to Fall böte dagegen reine Intensität. Also hören wir uns das auch gleich noch an.

Das Publikum ist längst außer sich, wenn Griot verklingt, die Spannung entlädt sich im finalen Track: Release is in the Mind. Ein Donnergrollen von Beginn an, was keinen Zweifel zulässt: es findet keine ruhige Heilung statt – eher eine explosive Katharsis. The Healing – die Heilung. Oder werden wir nicht vielmehr süchtig gemacht? Mit den besten Empfehlungen.

veröffentlicht am 14. Juni 2019

Rodrigo Amado tenor saxophone

Chris Corsano drums

All compositions by Amado / Corsano

Recorded by Joaquim Monte at Namouche Studios, Lisbon, July 14th, 2014

Mixed by Joaquim Monte and Rodrigo Amado

Mastered by Tó Pinheiro da Silva

Produced by Rodrigo Amado

Executive production by Nathan Cross

Design & Layout by Jaime Zuverza

von Rodrigo Amado & Chris Corsano

Veröffentlicht: August 2025

Ort: Lisboa, 2016

Link zum Album: rodrigoamado.bandcamp.com